This is the second post in a series on some of my favorite musicians from the ‘20s and ‘30s. Read the first one here.

Jimmie Lunceford and His Orchestra

James “Jimmie” Lunceford was a high school PE teacher in Tennessee when he formed what would become one of the most important jazz orchestras of the 1930s. Lunceford had taken music lessons as a boy from Paul Whiteman’s father, but unlike many other bandleaders at the time, his sole instrument was the conductor’s baton. The fact that he was able to turn a bunch of high schoolers into a jazz band that could make it in New York City—at the Cotton Club, no less—shows just how seriously he took leading the orchestra he created.

Fundamentally, Jimmie Lunceford was a dedicated showman. He valued precision playing and tighly-arranged swing compositions, but he contrasted these with vaudeville-inspired comedy bits, costume gags, and songs with outrageous lyrics.1 His tuxedoed bandmates were nicknamed “the trained seals” both for their ability to perform in perfect synchronization and for their willingness to do whatever tricks were necessary to keep the show moving. Lunceford wanted to give the audience a swingin’ good time, and did. Almost overnight, his orchestra was one of the most popular bands in America—their classy, meticulous, yet irreverent take on jazz and swing delivering a string of hit singles in the mid-1930s.

Like many other swing bands, Lunceford’s Orchestra performed a mix of syncopated jazz, “sweet” dance music, and vocal numbers. What set them apart was their lack of solos and the absence of trained singers. Lunceford preferred carefully-arranged and rigorously-rehearsed numbers to the wild freewheeling of traditional hot jazz, and it fit with his band’s madcap image to have the instrumentalists fill in as vocalists when the situation required.2 Sy Oliver, the band’s trumpet player, shaped the band’s distinctive sound, with the “one-two” Lunceford beat becoming the orchestra’s signature.

Jimmie Lunceford’s career was relatively short-lived. The coming of the Second World War wrecked the touring plans of just about every jazz band, as did the labor disputes between musicians, publishers, and radio networks that were paralyzing the industry in the early ‘40s. The rise of the crooners—namely Frank Sinatra—and the transition of many cutting-edge jazz musicians to bebop would soon make Lunceford’s swinging rhythms old hat. In 1947, while touring on the West Coast, Jimmie Lunceford died of a heart attack. He was only 45. His early death and the subsequent overshadowing of the swing era by a new generation of restless geniuses (Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Thelonius Monk, etc.) ensured that Lunceford would be essentially forgotten—a victim of changing tastes, short memories, and bebop.

Choice Tracks:

Annette Hanshaw

If Ruth Etting’s rise to stardom was a Hollywood tale of country girl making it in the big city through hard work and perserverance, Annette Hanshaw’s story was the opposite—a reluctant superstar who never pursued the limelight, but found herself there anyways. Though she came from a family of performers, Annette wanted to be an artist, only to be nudged into performing by friends and family who recognized her talents. After recording under a variety of aliases as a studio vocalist for a company that cranked out cheap records for dime stores, Annette developed a reputation in her own right as the “Personality Girl”—a reference to her trademark “That’s all” signoff at the end of recordings. She transitioned to radio, which she disliked, and her discontent with the showbiz life only grew with her fame. Despite being voted the most beloved female radio voice of 1934—Etting came in third—Hanshaw was already plotting her escape from the music industry. She recorded for the last time that same year, and had retired from radio by 1937.

Jazz historians generally agree that Hanshaw was a more talented singer and performer than Etting. She was versatile, able to improvise, and had an effortlessly spirited and charming delivery. Hanshaw, however, hated the sound of her own voice, and was never satisfied with any of her recordings. Today, we’d probably say shy, introverted, wildly talented Annette Hanshaw suffered from imposter syndrome—despite her success, she couldn’t believe she was as good as people said she was. “You just have to be such a ham and love performing,” she told an interviewer in 1972.3 Though she “loved… jamming with the musicians when it isn't important to do,” the fun was over as soon as the broadcast began or the recording started. She just couldn’t stand to sing if she knew people were listening.

Choice Tracks:

Artie Shaw

A young prodigy from New Haven who taught himself the clarinet as a teenager, Arthur Arshawsky was the unlikeliest jazz superstar. His parents were penniless immigrants, and the young Arshawsky experienced frequent discrimination because of his Jewish heritage. When he left home to persue a musical career at age 15, he discarded the Jewish-sounding Arshawsky and adopted the Anglicized professional moniker Artie Shaw. After ten years of playing in a variety of jazz bands, Shaw won a reputation as a promising composer and arranger, and soon was leading his own bands and surprising record executives (and himself) with his seemingly effortless ability to create catchy, classy, crowd-pleasing, danceable music. By the late 1930s, Shaw was literally the most popular musician in America, and he was baffled and frustrated by his own success.

Overbearing, opinionated, self-critical, and highly intelligent, Shaw thought swing music should be held to exacting standards of performance and artistic integrity that were usually associated with classical music. He despised the music industry, discarded bands as quickly as he formed them, and chafed against the expectations of managers and fans. His group’s theme song during its radio days, “Nightmare,” was a creeping, menacing dirge borrowing melodies from Shaw’s Jewish roots. He was one of the first bandleaders to add a string section to his band, just to keep things interesting, becoming an innovator in the blending of jazz music and classical (also known as “Third Stream”). He loathed having to play his biggest hit, “Begin the Beguine,” over and over—but that was what bands were expected to do in the ‘30s.4

Perhaps inevitably, Shaw grew bored and restless with what he derisively called “dance music.” He tried classical, and bebop, but eventually left music altogether in the 1950s, devoting himself to writing, reading, and making (generously compensated) public appearances. He would never play the clarinet again, though he continued to cultivate his public persona as an outsider whose music was too challenging for the industry.5 Despite his contempt for swing music, his recordings would signify the Swingin’ Thirties for generations of music fans and eventually film-goers. His talent for making what was essentially pop music seem elegant and sophisticated was unparalleled, and his self-conscious intellectualism, raging egotism, and restless creativity ensure he will always be a fascinating—and frustrating—figure in the jazz pantheon.

Choice Tracks:

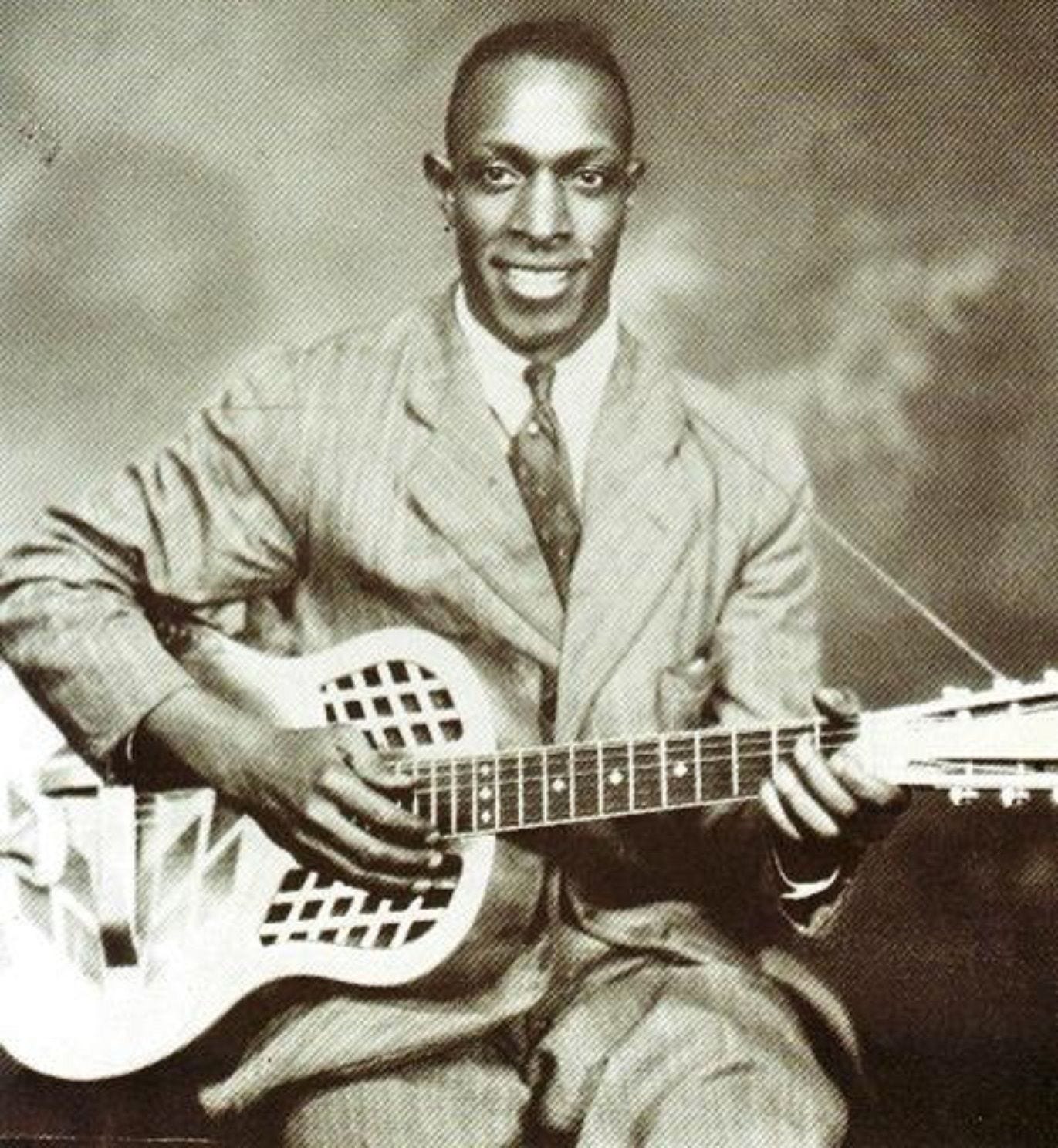

Peetie Wheatstraw

The Devil’s Son-in-Law. The High Sheriff of Hell. 1930s blues bad boy Peetie Wheatstraw knew how to sell himself. During his brief recording career (he died in a car crash in 1941), Wheatstraw built a reputation as a cocky, womanizing, devil-worshipping malefactor—one of the earliest examples of a formula embodied by everyone from Screamin’ Jay Hawkins to Marilyn Manson. His was music for the dregs of society—the black working men who frequented juke joints and other disreputable establishments—for whom hard work, hard times, and hard liquor were the only certainties. Wheatstraw slurred, moaned, wailed, hummed, and drawled his way through songs, throwing in an occasional “Oh, well, well” as if to remind his listeners that, devil-spawn though he may be, he was simply telling it like it is.

Like many blues artists at the time (and ever since), Wheatstraw essentially recorded the same song over and over again with different lyrics. He excoriated unfaithful women, fantasized about murder and revenge, offered commentary on current events, described the poverty and depravations of the Great Depression, boasted about his sexual prowess, and bemoaned his own bad luck. He was insanely prolific, recording 161 singles during his 11-year career—mostly plodding, piano-driven numbers, although he started adding warbling jazz horns to some of his later songs.6

While Wheatstraw’s music is best experienced in small doses, it can still transport you through time—back to the seedy juke joints of the 1930s, where drinking, gambling, dancing, and sex provided the only respite from a life of racist oppression and back-breaking labor. That may be what’s most fascinating about Wheatstraw—for all his self-styling as a social outsider and demoniac outlaw, his music embodied the struggles, prejudices, highs, and lows of what were, after all, ordinary people. Tens of thousands of black men worked in labor camps and factories across the nation, and in Peetie Wheatstraw, they found a swaggering, charismatic, talented performer who was just like them. He knew what it was like to lose a job, or lose a woman, or lose all your money at the craps table. He knew what it was like to long for just a little good luck for a change—even if that good luck came from the Devil himself.

Choice Tracks:

See “Miss Otis Regrets” and “Unsophisticated Sue.”

Besides the fact that many members of the band were not half-bad behind the mic, it also makes the comic numbers twice as funny for them to be sung by someone who sounds like an Average Joe rather than, you know, Bing Crosby.

In the same interview, Hanshaw admits that money was a major consideration in her continuing her music career despite her strong dislike of performing: she was making thousands of dollars an hour for her songs. When she retired in the mid-1930s, Hanshaw was certainly a millionaire many times over.

Cab Calloway estimated that he’d performed “Minnie the Moocher” 40,000 times between its release in 1931 and its “12th birthday” in 1943—or just under ten times a night. This tallies with what Shaw said about how many times he was expected to play “Begin the Beguine” when playing hotel and nightclub engagements.

Personally, I find Shaw’s posturing hard to take seriously. Plenty of his contemporaries (Duke Ellington and Stan Kenton come to mind) managed the transition from mainstream bandleaders to critically-acclaimed experimentalists in the ‘50s and ‘60s. I suspect that, despite his discomfort with the demands of the music industry, Shaw liked being famous and playing to packed halls and adoring crowds, and found the ambivalent popular reception of his forays into classical and bebop frustrating and dispiriting. A psychologist (and psychoanalysis was very popular in those days) would probably trace these feelings back to Shaw’s childhood, when, bullied for his Jewish heritage, he turned to music as a way of gaining acceptance. Whatever the case, Shaw was talented and creative enough to make the jump to Third Stream jazz or bebop—he just didn’t think it was worth his while.

Volume 7 of Wheatstraw’s complete works, released by Document Records in 1994 and covering the years 1940-1941, showcases his move towards cleaner production and more pronounced jazz influences. The jazzy flourishes made his music a lot less repetitive, and this period (which came right before his death) is easy his most accessible.