This week, Marbrose City Music returns for the first in a two (or maybe three?) part series showcasing my favorite musicians from the Jazz Age—a term which I will be (somewhat idiosyncratically) using to refer to the period of American pop culture that stretches from the beginning of Prohibition to the outbreak of World War II. The standard objection to such a construal is that the Wall Street Crash (and later, the repeal of Prohibition) were significant turning points in American culture, and that, by 1933, most of the Roaring Twenties excess and swagger had gone out of American life, never to return. As F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in 1931, the Jazz Age “leaped to a spectacular death in October, 1929,” and you would think he would know.

There may be something to this from a societal perspective, but musically, the two decades from 1919 to 1939 show a great deal of continuity. Many of the biggest artists of the 1920s—Paul Whiteman, Duke Ellington, Guy Lombardo—maintained their popularity well into the ‘30s, and new musical trends (like swing) had firm roots in the hot jazz of the Roaring Twenties. More quirky stars who sang through their noses like Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor were replaced by smooth-voiced crooners like Bing Crosby (and, eventually, Frank Sinatra), but the basic format of popular music—jazz and dance orchestras playing music driven by piano, bass, and brass—remained the same. There were no musical revolutions in the 1930s, only evolution. Even the emergence of blues was merely the record industry discovering the commercial potential of a style that already existed outside of the mainstream.

So, we’re sticking with the term “Jazz Age.” Call it the “Long Jazz Age” if you prefer.

As with everything posted in this blog, the thoughts below reflect my rather unsystematic knowledge of 1920/1930s jazz rather than some official consensus among music critics and historians. I’ve always chosen my own interests, and so my knowledge of music comes entirely from reading stuff on the Internet and listening to it myself.

Cab Calloway & His Orchestra

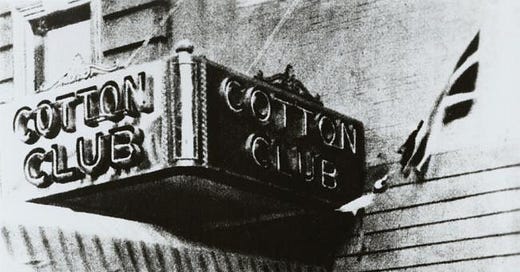

Like Duke Ellington, whose band he replaced at Harlem’s Cotton Club, Cab Calloway was born into a middle class African American family and grew up in eastern Maryland surrounded by the best of black culture. As young men, both chose not to follow their parents into careers as respectable black professionals, and instead became musicians—a path that would ultimately take them to Manhattan and the heart of the Harlem Renaissance. As musicians, however, the two men were quite different. The Duke was a genius—a prolific composer whose talent would only mature with age. Cab, on the other hand, was a performer—a Jazz Age rock star whose charisma, outlandish sense of style, and proficiency in the argot of Harlem’s jazz counterculture made him one of the most recognizable figures in the 1930s. He was frequently caricatured in the cartoons of the period, and his 1931 megahit “Minnie the Moocher” appeared in a Betty Boop short and jokes by the Marx Brothers.1 It spawned imitations, parodies, and responses from other artists, which Calloway encouraged by writing further songs about its protagonists, Minnie and Smoky Joe, and their drug-addled adventures in Chinatown.

While Cab’s orchestra did perform instrumental music, it was his jivin’, scattin’, howlin’ vocals that were the star of the show. This set him apart from other bandleaders of the period, who usually conducted or perhaps played the piano. Cab put his personality and performance, not his reputation as a songwriter or musician, front and center. Cab danced while he sang, engaged in call-and-response with the audience, and played fast-and-loose with the lyrics. Audiences in the 1930s had never heard anything like it, and they loved it. Calloway came to represent the coolness of Jazz Age Harlem to the American public, and he obviously relished the task.

Choice Tracks:

Ruth Etting

The iconic nightclub singer of the 1920s, Ruth Etting combined a talent for girlish crooning with the brash sex appeal (or “it,” as it was called in those days) of a gangster’s moll. Getting her start as a chorus girl in Chicago nightclubs, Etting eventually made her way to the Ziegfeld Follies in New York, and from there to Broadway and Hollywood. Originally a country girl from Nowheresville, Nebraska, her marriage to Martin “Moe the Gimp” Snyder, a Jewish gangster, was initially a boon for her career. Moe was a pushy promoter, elbowing Etting into singing gigs and forcefully asserting her interests to bandleaders, record executives, and Broadway producers. Eventually, Moe’s reputation as a difficult manager and tendency to antagonize men who were more powerful than he was (notably Flo Ziegfeld) started to close doors for Etting, and she divorced her thuggish husband in 1937. Though Moe the Gimp didn’t contest the divorce, he attempted to kill her new boyfriend in 1938, creating a public scandal that effectively ended her career as a Jazz Age pop superstar.

While promotional images of Etting were quite saucy (usually featuring “ample epidermis,” as they said in the ‘20s), her songs usually presented her as a jilted everygirl pining after lost love, and she played the role to perfection. Perhaps more than any other female singer, Ruth Etting embodied the aspirations of young women in the Jazz Age. She was the country bumpkin who made it on Broadway—the plot of many a silent film—yet she sang about the everyday struggles of break-ups and neglectful boyfriends and romantic uncertainty. She brought the glamor of the big city to the heartaches of girls in small-town America, using records, the radio, and eventually motion pictures to go from the “Sweetheart of Chicago” to the darling of the whole nation.

Choice Tracks:

The Boswell Sisters

The three-part hamonies, rapid-fire scatting, and shuffling rhythms of the Boswell Sisters were cutting edge in an era when most white audiences wouldn’t listen to anything jazzier than Paul Whiteman.2 The trio originated in New Orleans, and incorporated hot jazz influences into their unique sound, which treated their voices like the syncopated brass section of a jazz band—unsurprisingly, all three sisters were instrumentalists before they took up singing. Drawing freely from jazz, swing, country, calypso, ragtime, and blues—sometimes in the same song—their music is playful, and often features sudden shifts in rhythm or tempo. Given their strong musical background and the consistency of their style over the years, it’s hard to escape to conclusion that Martha, Connie, and Vet were, unlike many other vocalists at the time, in creative control of their own music.

Despite their relatively brief career (the group disbanded in 1936 after Martha got married), the Boswell Sisters were hugely influential on American popular music. Ella Fitzgerald was a fan, and so were the Andrews Sisters, who took the Boswell’s style to even larger radio audiences in the 1940s. Their habit of bringing together several different styles in one song makes their music a whirlwind tour of pop trends in the early 1930s, and an excellent case study in just how blurry the lines between jazz, pop, country, and the blues could be in the Interwar Years—and especially in New Orleans.

Choice Tracks:

Fletcher Henderson & His Orchestra

Probably the most influential jazz band you’ve never heard of, Fletcher Henderson and His Orchestra were quite well-known in the Manhattan jazz scene in the 1920s. A brilliant musician and a notoriously bad manager, Henderson’s unique take on jazz won him many admirers (including Duke Ellington) but little in the way of financial success. Together with arranger Don Redman, Henderson pioneered the jazz band as “orchestra,” with expanded brass and woodwind sections and an emphasis on rhythmic interplay (“call and response”) between the two. The result was a less polyphonic and more structured take on jazz with a fuller, cleaner, “classier” sound. But, with his chronic inability to hold onto money and sidemen, Henderson watched many of his contemporaries (and former bandmates) achieve fame and fortune in the late 1920s while he struggled to hold his orchestra together.3

National success for Henderson would come only vicariously, when Benny Goodman,4 who needed material for his radio show, approached Henderson to create a new repetoire for his band. Henderson supplied Goodman with a mix of old songs and new arrangments, and in the process introduced listeners across America to the genre he helped create: swing. Eventually joining Goodman’s band full-time, Henderson would become known mainly as an arranger, with all the fame (and credit) for swing in the popular imagination going to white musicians like Goodman, the Dorsey Brothers, and Glenn Miller. Yet without Henderson, there would have been no Swingin’ Thirties, and probably no one to challenge the mainstream dominance of “sweet” dance music.

Choice Tracks:5

To be continued.

See 1935’s A Night at the Opera, also the source of the infamous “Sanity Clause” line.

Paul Whiteman was probably the most successful bandleader of the 1920s, playing what was known at the time as “sweet” jazz. Whiteman’s approach was (and is) controversial—basically, he was accused of presenting a watered-down take on jazz to appeal to white audiences, while also claiming to be “the King of Jazz”—but his African American contemporaries thought highly of him, both as an artist and a supporter of the more “authentic” jazz scene (where most of the musicians were black).

The most notable former Henderson sideman was Louis Armstrong.

Probably the only American musician to become a pop superstar by playing the clarinet.

The tracks listed below were recorded in a series of sessions for Decca in 1934, but most of them had been in Henderson’s repetoire since the mid ‘20s.