Silence & Silver 27: Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925)

Revenge, Redemption, and Lots of Dead Horses (Christmas 2024)

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ is not a nice Christian film.

It’s violent, even by modern standards. It plays to the audience’s thirst for blood and spectacle with its grisly battles and scenes of Roman brutality and decadence. Judah Ben-Hur’s (Ramon Novarro1) quest for revenge against Messala (Francis X. Bushman), the man who destroyed the House of Hur, takes him from the slave galley of a Roman warship to the race track at Antioch, where he wagers his entire fortune against the Roman in a chariot race to the death. The sets are colossal—more imposing, even, than the Art Deco palaces in The Thief of Bagdad (1924). The seamless blending of magnificent temple and mansion sets with matte paintings of Jerusalem and Antioch give a sense of classical scale and archaic grandeur that few modern films can capture. This is a biblical epic—reimagined as a dystopian tale of hatred and vengeance set against the glory and oppression of Rome. The gladius and caliga of Rome is omnipresent—inflicting injustice on rich and slave alike. The galley scene, where a slave chooses to be flogged to death instead of continuing to suffer behind the oar, is the most horrifying image in a movie filled with brutality.

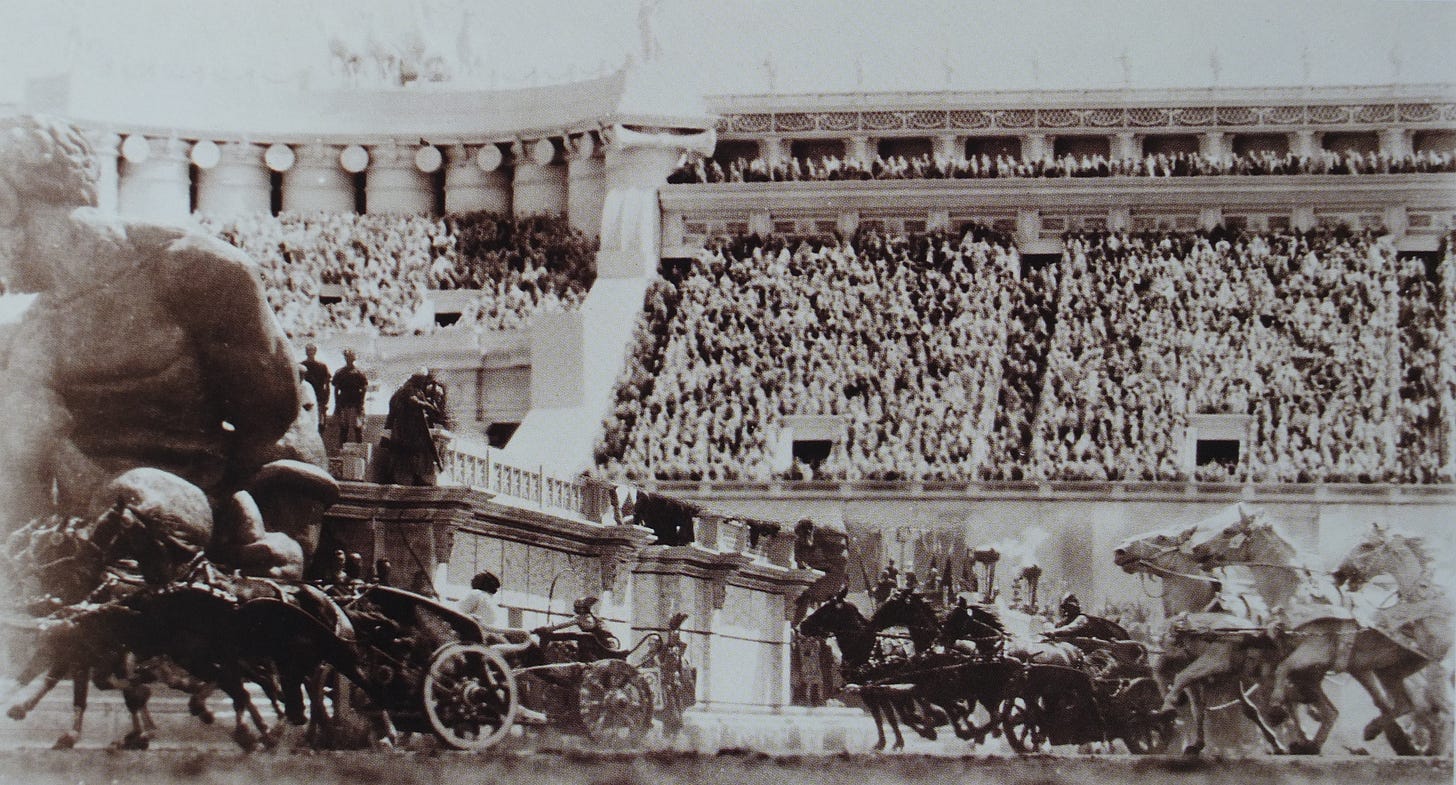

The chariot race is the most famous sequence—imitated not only in later remakes of Ben-Hur but also in the podrace scene in The Phantom Menace.2 Filmed in a massive Roman-style racing stadium constructed on a corner lot in Los Angeles,3 the final showdown between Judah and Messala is Hollywood spectacle at its finest. It’s shot like an auto race—a parallel audiences in the 1920s would have immediately recognized—cutting back and forth between the cocky Messala in his winged helmet and obsessive, stone-faced Ben-Hur as they speed down the track. Dozens of horses perished while filming the dangerous sequence—the stuntmen had been promised a reward for the race’s winner, and so raced with the desperation of real competitors. The crashes were deliberate, but perfectly real—five horses were killed when Messala’s chariot wrecks on the final lap, although this was concealed from the audience of toga-wearing spectators, which included Hollywood luminaries like Mary Pickford and Harold Lloyd.4

I have to take back something I said earlier. Despite its callous violence and pulpy thrills and wanton disregard for animal welfare, Ben-Hur really is a nice Christian film. Judah’s successful quest for vengeance against Messala and Rome leaves him empty, and he only finds purpose when he sees the Nazarene—who he wants to enlist as the leader of an anti-Roman military coalition funded by the Hur fortune—dragging his cross through the streets of Jerusalem. Jesus himself is treated with reverence that goes beyond even the original Lew Wallace novel—he appears only as a hand, reaching out to teach, heal, and bless. Many of the intertitles—especially at the beginning and end of the movie—are passages from the New Testament. The scenes about Jesus are filmed in red-green Technicolor—a strange but effective way of conveying holiness.

More importantly, the final third of the movie is entirely about the hope of forgiveness and resurrection. Jesus literally brings a dead child back to life as he staggers towards Golgotha, and heals two lepers—Judah’s lost mother (Claire McDowell) and sister (Kathleen Key)—in his last miracle before his execution. During the film’s first two acts, Judah’s hatred for Rome turned him into a Roman—first in attitude, then (after he’s adopted by Arrius) in cold, legal fact. Judah’s encounter with Jesus forces him to see himself—to understand how his hatred for Rome has come to rule him. In the exact moment that Judah finally abandons the way of the sword and the jackboot, the mother and sister he thought were dead are restored to him. Rome will conquer and rule, but the way of Rome—the way of violence and revenge—cannot give life. The bloody footprints that Jesus of Nazareth leaves on the cobblestones of Jerusalem show Judah Ben-Hur a different way—the way of forgiveness.

Postscript: So, besides all the Jesus stuff, what does this movie have to do with Christmas? Well, two things. First, the film’s prologue is basically a Christmas pageant with a Hollywood budget, complete with shepards, wise men, and a shining star over Bethlehem. This seems irrelevant, even after Judah meets a kindly carpenter who gives him a drink as he marches into slavery in the galleys. But when Balthazar, the Egyptian wise man, reappears at the start of the third act, it all comes together—Judah chooses Jesus to lead his revolution against Rome, setting him on the path that will reunite him with his family and lead to him renouncing violence and revenge. Balthazar is a more significant character in the novel—Iras (Carmel Myers), Messala’s vampish girlfriend, is his daughter, something the movie leaves unclear. Like the Gospel of Luke, which it frequently quotes, Ben-Hur begins in Bethlehem and ends in Jerusalem. It just takes a different way to get there.

(Also, the 1920s isn’t exactly bursting with Christmas movies. We’ll take what we can get.)

Rudolph Valentino turned down the part, and George Walsh was actually cast as Ben-Hur, but fired and replaced by Novarro during filming. Walsh, who was on location in Italy, learned that he’d been replaced from the newspapers.

I’m not going to say Episode I is a misunderstood masterpiece, but it is the creation of someone who really, really likes the epics and adventure films of the ‘20s and ‘30s.

Filming was supposed to take place in Mussolini’s Italy, although just about everything that could go wrong did, and the filming eventually relocated to California after wasting about 2 years and $3 million dollars on unfinished sets, unreliable extras, and dangerous shoots.

These anecdotes are taken from film historian Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By… Brownlow quotes Francis X. Bushman as the source for the claim that more than a hundred horses were killed in the unused Rome shoot alone. Second unit director B. Reaves Eason was notorious for treating horses as disposible during filming—he later killed 25 horses with tripwires while filming The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), which is one of the main reasons why films since have been monitored by the ASPCA.