This post is going to be a bit like me explaining to you why you should watch The Godfather, or read Les Miserables, or listen to the Beatles.

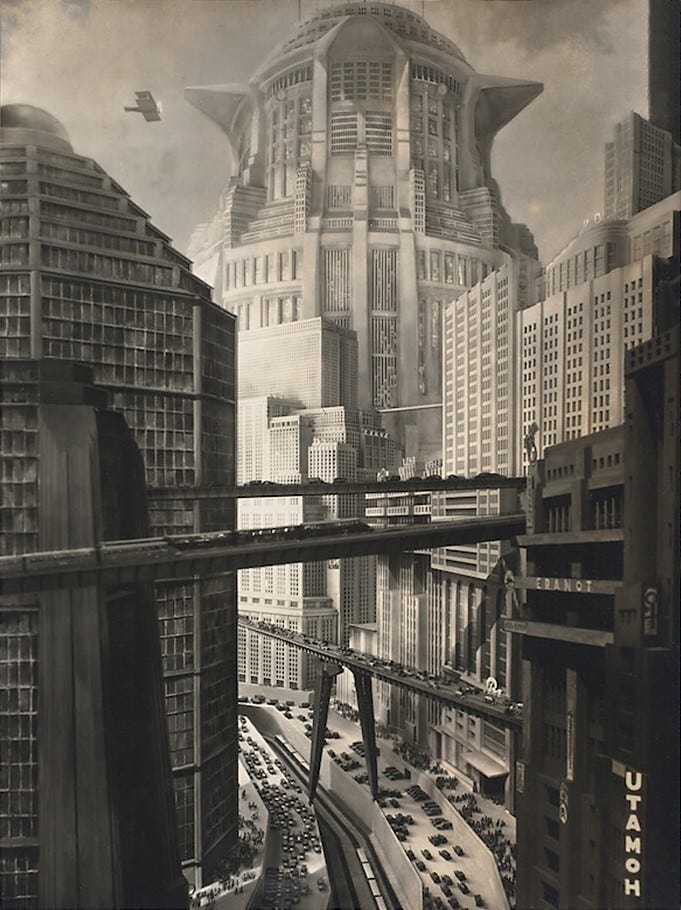

Metropolis, after all, is probably the most famous and critically-acclaimed silent film of all time. Its imagery has been borrowed and re-borrowed so many times that it’s become part of our collective cultural unconsciousness. The tropes it established—the sleek android and its mad scientist creator, the robotic hand under the black glove, the futuristic shining city built on a sinister foundation—seem almost timeless and universal, as though they always existed. And, in a way, they did. Metropolis draws on everything from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to Peter Bruegel’s paintings of the Tower of Babel to stories of human sacrifice to the Canaanite god Moloch1 in the Old Testament. Its plot is Johannine and gnostic: a savior figure from the world above descends into the depths to become a mediator for the downtrodden, motivated by love of mankind. What’s unique is that it gives these ideas striking visual and dramatic expression. Metropolis is the first truly cinematic dystopia—its soaring towers, titanic machines, and masses of workers marching in lockstep have haunted us ever since.

But, let’s assume you know nothing whatsoever about this movie beyond what I’ve already said about androids and mad scientists and futuristic cities. What the heck is Metropolis about, anyways?

Well, like more-or-less every German Expressionist film, Metropolis is about the political and economic conditions in Germany in the 1920s. But if you’re not me, that probably doesn’t sound too exciting. So let me try again: Metropolis is about a vast, towering city of Art Deco monoliths, powered by workers slaving away at gigantic machines deep beneath its foundations. The man who made this city of tomorrow, Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel), sees this arrangement (in which he, “the Head,” rules the workers, “the Hands”) as fundamentally just. But in the darkened depths of Metropolis, the undercity where the workers and their children dwell, a young woman named Maria (Brigitte Helm) preaches the coming of a mediator—”the Heart”—who will make peace between the Head and the Hands. Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), the son of the great industrialist who rules Metropolis, believes he is destined to become the Heart and save the workers from their plight.2 Meanwhile, Rotwang (Fritz Rasp), a mad scientist with a prosthetic hand, has created a robot in the image of Hel, Joh Fredersen’s dead wife, and plans to use his creation to take revenge on the man who took everything from him.

Director Fritz Lang was, in later years, dismissive of the themes of Metropolis, feeling them to be too pat and simplistic to speak to the real world.3 But that’s exactly the point. Metropolis is, in Lang’s own words, a fairytale. Its world is strange and dreamlike—Wagnerian in its pathos and scale. The performances aren’t subtle, but—like in an opera—they don’t need to be. Lang drove the actors like a madman, shooting scenes over and over again in extreme conditions to get exactly the emotions he wanted. The sets, like the backdrop to Aida or Götterdämmerung, are colossal—echoing both ancient ziggurats and modern Art Deco skyscrapers. The machines, perhaps the film’s unspeaking antagonists, symbolize the crushing mechanization of modern life in their senseless whirring and pulsing and hissing of steam. “Moloch!” cries Freder when he first sees them, but as the plot unfolds, an even more horrifying truth emerges: by design, the workers need the machines, and so cannot free themselves from them except in an act of self-destruction.

The special effects really are incredible. Silent films, even at their best, usually require a pretty radical suspension of disbelief with their use of stop-motion and miniatures. Not Metropolis. Lang was determined to beat Hollywood at its own game, and did. The detailed miniatures, the mesmerizing camera work, the animation, the machines—it all comes together to create a complete cinematic world that would not be equaled until another director—a young dreamer from Modesto, California—set out to create his own story of a shining robot, a father and son in conflict, and a spiritual rebellion against the authoritarian mechanization of existence.4

I would be amiss if I didn’t conclude with Brigitte Helm’s incredible double-performance as Maria and the Machine-Man who impersonates her. It’s a transformation worthy of John Barrymore as Jekyll and Hyde, made more impressive by the fact that Helm does nothing but change her eye makeup.5 The real Maria is compassionate, idealistic, and selfless—a living saint bringing light to the darkness of the city’s forgotten catacombs. The imposter is a maniacal demon, relishing the strife she sows and chewing so much scenery it’s remarkable there’s any left for anyone else. The hunger and animalism of her movements is all the more shocking for their contrast with the meek, maternal nature of her alter-ego. When Freder exclaims “You are not Maria,” it’s the audience shouting too.

And that’s the thing about Metropolis. It’s a movie of strong feelings and arresting images. It’s a story that expresses deep human longings and profound modern discontents, while offering a message of hope. Perhaps Lang is right, and his movie is ultimately too optimistic about the reconcilation of labor and capital (or those who work with their hands and those who work with their minds, or however you choose to interpret it). But as a cinematic opera of ideas and passions—as an expression of timeless cultural symbols and yearnings—Metropolis transcends any particular interpretation. It’s about class relations in Weimar Germany, but it’s also about us, now.

For Moloch is always with us, and he is always demanding new sacrifices.

Postscript: Almost immediately after Metropolis was released, distributors started trimming down Lang’s ponderous epic to something a little more approachable. That means there are several different versions of Metropolis out there, of varying length and quality.6 You’re looking for the 2010 restoration, which is missing just a few minutes of the original film. Some of the scenes are grainier and have a different aspect ratio, since the rediscovered film used in the restoration had been trimmed for a different sized screen.

The ancient Canaanites certainly practiced child sacrifice. However, there is debate among Biblical scholars as to whether Moloch (Hebrew mlk) was an actual deity or simply the name of the child sacrifice custom. There is, likewise, some dispute over whether the Carthaginans offered living children as burnt sacrifices to their gods. Lang likely got the idea from the 1914 Italian epic Cabiria, which is set during the Second Punic War and features children being fed into a fiery statue of Moloch.

This initially has more to do with his infatuation with Maria than any profound sense of destiny, but you’ll be surprised how far it gets him.

The film’s broad themes meant that it found admirers among Nazis and Communists alike. In 1933, Joseph Goebbels tried to enlist Lang, who was of Jewish descent, to make Nazi propaganda movies, which inspired him to leave Germany for good and ultimately emigrate to the United States. His (ex-)wife, Thea von Harbou, with whom he wrote Metropolis, was a Nazi sympathizer and remained in Germany, becoming a willing tool of the Third Reich in the arena of film.

“Yeah, but his shining robot wasn’t as sexy.” - My wife, who apparently holds a low opinion of C-3PO.

Helm also plays the Maschinenmensch (Machine Man) in its robotic form, but the costume was uncomfortable and restricted her movements, so it’s only used in a few scenes. They make a heck of an impression, though.

Most notoriously, Giorgio Moroder edited the film down to a paltry 83 minutes and added a new soundtrack of upbeat 1980s pop music (I’m not joking) that’s about as disconnected from the look and themes of the original as it’s possible to be.